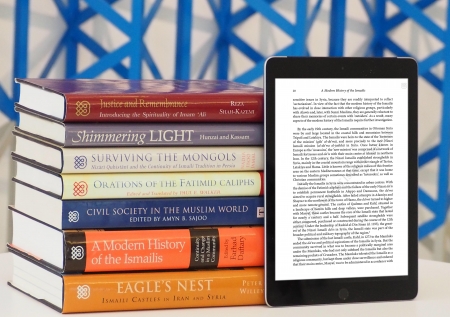

Set on its own terraced rise from Ismail Somoni Avenue in the heart of Dushanbe, the Ismaili Centre presents a stately landmark on the inner fringe of a growing metropolis. Situated on a major thoroughfare, the Centre complements prominent public spaces in its proximity, from the Kohi Borbad Concert Hall to Lake Komsomol. Readily accessed from beyond the oak trees along the quieter Sportivnaya Street, the Centre projects a reassuring sense of continuity. Exquisitely embedded within each of its five dignified oblong minars in blue and turquoise glazed brick is calligraphy in stylised kufic acknowledging the singularity and majesty of the Almighty.

Award-winning Canadian architect Farouk Noormohamed brought an acute sensitivity to integrating social and cultural specificity into cosmopolitan settings. Conscious of the region’s seismicity, he assured an elastic roof diaphragm that is designed to transfer stress to supporting elements of the overall structure. Other innovations include a heating and air conditioning system based on water-source heat pumps used for the first time on this scale in the region, and a heat recovery wheel for energy efficiency. Meanwhile, the Centre’s underground parking area improves access and safety.

The visitor follows gradations upstream along a soothing watercourse to the main entrance. Under the resplendent canopy, a more humble design draws on the traditional Pamiri chorkhona, a skylight in layered concentric squares recalling ancient philosophical symbols for earth, water, air and fire that became assimilated into the cultural traditions of Central Asia. Repeated frequently throughout the Centre like the chorkhona, a brick-like pattern on the massive wooden portals represents the char bagh promised in the courtyard now distantly perceptible.

Pausing at the octagonal foyer, one senses quiet alcoves, their repetitive inflexions and the interplay of shafts of light from symmetrical latticed stairwells. Continuing along the main axial atrium, the visitor is at once absorbed into the intricate floral geometry along one wall but also conscious of a changing heavenly firmament. Intermediating natural radiance from above, masharabiyya continually transform shadows according to a circadian rhythm. On either side of the corridor, administrative offices and meeting rooms quietly assure the operation of the Centre and its activities.

In the courtyard, Persian silk trees shade fountains and interconnecting channels, their serenity protected by four iwans evoking the Quran’s metaphors of gardens with flowing streams. Surrounded by classrooms and teaching resources and open to the sky, this tranquil space facilitates interaction with a knowledge centre that is furnished, wired and connected.

The Ismaili Centre, Dushanbe is equipped to host conferences, lectures and cultural performances. Translation booths permit simultaneous multilingual translation of proceedings. Elaborate floral plasterwork, a meticulous suzani tapestry and the courtyard view delineate the Forum’s kaleidoscopic potential. Encyclopaedic in his reach, Abu Nasr Farabi, besides being known as a master of languages, logic, political philosophy, ethics and metaphysics, also composed music; melodies in Anatolian music and raags in classical North Indian music are to this day attributed to him.

In the tradition of Muslim piety, for centuries, a variety of spaces of gathering have co-existed harmoniously with the masjid, which itself has also accommodated diverse institutional spaces for educational, social and reflective purposes. These spaces, that have historically served communities of different interpretations and spiritual affiliations, have retained their cultural nomenclatures and characteristics, from ribat to zawiyya to khanaqah and jamatkhana. In keeping with these historical precedents, the jamatkhana is space that is reserved for practices of Shia Ismaili Islam, and a place which inspires the community’s engagement with the larger world as a direct extension of the ethics of the faith .

Contemplative pools in serene corners of northern loggia focus the visitor inwards. . Progression into the jamatkhana, traversing now both aesthetic harmony and historic memory, becomes an interior journey.

Invisible behind wood panelling, beams of steel provide the structural support that permits an open, column-free space to the ceiling above.

Within its layered and interconnected spaces, the Ismaili Centre, Dushanbe engenders a spirit of openness and tolerance, of sharing and exchanging, of recollection and inspiration. Like the landscaped gardens that enfold the complex, these interiors presage enlightened encounters between the past, the present and the future.