The spread of false information during the coronavirus outbreak has been rapid, with well-meaning friends and family sharing messages on WhatsApp and Facebook warning of everything from premature government lockdowns to unusual home remedies that claim to beat the virus.

“We’re not just fighting an epidemic; we’re fighting an infodemic,” said Tedros Adhanom Ghebreyesus, Director General of the World Health Organisation. “Fake news spreads faster and more easily than this virus, and is just as dangerous.”

It’s likely we all know someone who has unfortunately shared inaccurate information about the risk of the outbreak, however, according to research, it likely wasn’t intentional.

Studies indicate that 46 percent of Internet-using adults in the UK viewed false or misleading information about the virus in the first week of the country’s lockdown. Furthermore, researchers at King’s College London questioned people about Covid-19 conspiracy theories, such as the false idea that the virus was linked to the rollout of 5G mobile networks. Those who believed these theories were less likely to believe there was a good reason for the lockdown in the UK, potentially increasing the risk to their health if they chose to ignore government instructions.

These forwarded messages may contain useless, incorrect, or even harmful information and advice, which can hamper the public health response and add to social disorder and division.

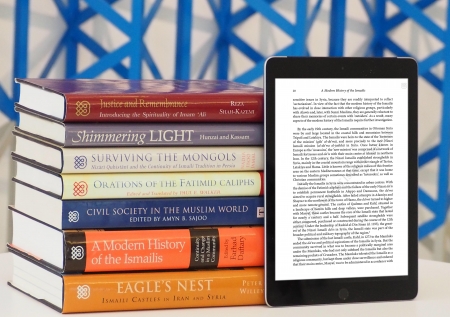

Even within our own community, the temporary closure of our Jamatkhana spaces has resulted in the appearance of “virtual Jamatkhanas,” the details of which were forwarded onto many others without a second thought. These virtual gatherings are not appropriate, as Jamatkhana may only be established by the Imam-of-the-Time, through his institutions and appointed Mukhi-Kamadias.

Additionally, a recent report from one province in Iran found that hundreds of people had died from drinking industrial-strength methanol — based on a false claim that it could protect from contracting Covid-19.

Regardless of the consequences of taking notice of fake news, the “infodemic” will likely continue. While companies such as Instagram, Facebook, and Twitter have introduced new measures (Facebook recently introduced an Information Centre with a mix of curated information and medical advice), we must be proactive and act rationally, with prudence and sound judgment.

In East Africa in 2016, Mawlana Hazar Imam explained that digital mediums have produced a global flood of voices in the form of websites, blogs, and social media, saying that, “The result is often a wild mix of messages: good information and bad information, superficial impressions, fleeting images, and a good deal of confusion and conflict. And this is true all over the world.”

At a time of intensifying emotions and growing polarisation, this is resulting in a society in which people feel “entitled to their own facts.”

“In such a world, it is absolutely critical – more than ever – that the public should have somewhere to turn for reliable, balanced, objective, and accurate information,” Hazar Imam continued.

In a world filled with a mixture of information, what do these dramatic changes mean for the Jamat worldwide? Here are some research-backed suggestions to combat misinformation:

- Source: Question the source - references have been made to lots of institutions and experts during this outbreak. Check on official mainstream media to see if the story is repeated there. If it was forwarded from a “friend of a friend,” assume it’s a rumour, unless proven otherwise.

- Use fact-checking websites: Websites like APFactCheck and FullFact separate out true claims from false ones. While it’s far easier to just forward a WhatsApp message that someone else sent to you, a quick search on fact-checking sites will inform you if it’s been flagged as fake news by more trusted sources.

- Over-encouragement to share: Be wary if the message asks you to share - this is how viral messaging works.

- Listen to advice from official institutions: the best places to go for health information about Covid-19 are government health websites and the World Health Organisation website.

At this time in particular, it is critical that we understand the risks of misinformation and miscommunication, and rely only on credible government and Jamati institutional sources, such as The Ismaili, the official website of the Ismaili community.

If we are mindful of our own online behaviour and think about the factual basis of the news we consume and forward on, we can stem the spread of misinformation while helping one another to decide what to trust for the betterment of our lives.